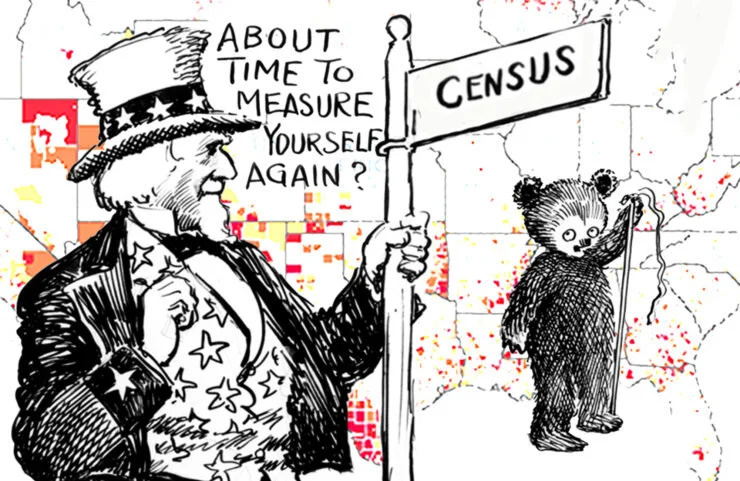

Census Bureau’s Way of Counting of Prisoners Erodes “One Person, One Vote”

https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/politics/2021/10/20/wisconsin-voting-districts-skew-power-small-prison-towns/8536983002/

Since its first count in 1790, the Census Bureau has counted incarcerated people as residents of wherever they’re incarcerated at the time of the census — as opposed to where they call home — even though in 48 of 50 states, they cannot vote in that community, or anywhere. In effect, this transfers each prisoner’s vote to another voter in the district, undermining the "one person, one vote" principle of American democracy.

Social Distancing Is The Law, But How Do Police Enforce It?

Since New York’s North Country began to reopen, one big question is what if people don’t follow the rules? And what exactly even are the rules? On the front lines of these questions are local police, but how to enforce public health is something officers are figuring out as they go.

Since New York’s North Country began to reopen, one big question is what if people don’t follow the rules? And what exactly even are the rules? On the front lines of these questions are local police, but how to enforce public health is something officers are figuring out as they go.

Don't Count on the Census

The results of the 2020 federal census will have a huge impact on the country over the next ten years - but in Wisconsin, mass incarceration of African-Americans is skewing the count. In a practice known as “prison gerrymandering”, inmates are counted in the district where they are imprisoned instead of the place they call home. This has the effect of shifting political power away from urban black communities and giving disproportionate representation to certain rural white populations.

When the Census Bureau comes around this April, it will be counting nearly two million people in the wrong place: in the place where they are incarcerated, not where they call home. What started as a quirk in the way we count people behind bars now serves to reinforce some of our country's ugliest racial and political dynamics. This practice, called "prison gerrymandering," happens all over the country, but some of the most dramatic examples are playing out in Wisconsin, where as a result political power gets diluted in urban black communities and concentrated in rural white communities where prisons are built.

1st Massachusetts Prisoner To Apply For Compassionate Release Awaits Answer

If someone in prison has a terminal illness and poses no risk to society, they should be allowed to die at home — that's the idea behind what's called "compassionate release." So far, 49 states have adopted the policy. Any day now, the first prisoner in the Massachusetts correctional system to apply for compassionate release is due a final answer.

If someone in prison has a terminal illness and poses no risk to society, they should be allowed to die at home — that's the idea behind what's called "compassionate release." So far, 49 states have adopted the policy. Any day now, the first prisoner in the Massachusetts correctional system to apply for compassionate release is due a final answer.

For Two New Hampshire Women, the Issue of Immigration is Personal

Pam Colantuono and Minata Toure have never met, but they have a few things in common. They both live in Manchester, they’re both moms. The biggest thing they share — the thing that shapes both their lives and how they see the world — is the classic American immigration narrative.

Pam Colantuono and Minata Toure have never met, but they have a few things in common. They both live in Manchester, they’re both moms. The biggest thing they share — the thing that shapes both their lives and how they see the world — is the classic American immigration narrative.

How Much Can New Hampshire's Governor Actually Do? Not Much.

New Hampshire voters had the biggest field of candidates for governor to consider in 20 years--seven people wanted the job. But how much can a New Hampshire governor actually do, anyway?

New Hampshire voters had the biggest field of candidates for governor to consider in 20 years--seven people wanted the job. But how much can a New Hampshire governor actually do, anyway? As it turns out, if you’re governor of New Hampshire, you’ve been handed a pretty raw deal.

Homeless at The P.K. Motel

It’s nearly impossible to say how many homeless people there are in New Hampshire. And the biggest reason is that most people without a home in this state aren’t on the street or in shelters—they actually have a roof over their heads.

The PK Motel rises up over a big, dusty parking lot, part way down a rural road in Effingham, close to the Maine Border and wedged between the lakes and the White Mountains. The place looks more like a warehouse than a motel. It's not a place families stop on vacation. It's where local town welfare offices send people when they're out of options. And behind each of these doors are stories of people stranded by poverty - stories about addiction, violence, rural isolation, bad luck, and bad choices.

This story is part three in a special series on homelessness in New Hampshire:

http://www.nhprdigital.org/series-homeless-in-nh#special-series-homeless-in-nh

Are New Hampshire Cities Asking Homeless People to Disappear?

Drive the highway between Manchester and Concord, and maybe you’ll catch a glimpse of the tarps and tents lining sections of the Merrimack River and the train tracks. When winter shelters close, homeless people find refuge outdoors, in public—but that’s an act that’s often against the law.

Some cities in New Hampshire have backed away from rules against camping or panhandling, while others still choose to enforce them. And through these layers of conflicting policy, it’s unclear for homeless people what their rights actually are. Which means if you’re living on the streets of New Hampshire’s cities, you’re expected to pull off a kind of magic trick: make yourself disappear, right in plain sight.

This story is part two in a special series on homelessness in New Hampshire:

http://www.nhprdigital.org/series-homeless-in-nh#special-series-homeless-in-nh

What Happened to Gene Parker?

This past winter a car struck and killed a homeless man in Concord. His name was Gene Parker - he lived on the streets for five years and in that time his friends and advocates fought hard to get him into an apartment. But he died before that could happen.

This past winter a car struck and killed a homeless man in Concord. His name was Gene Parker - he lived on the streets for five years and in that time his friends and advocates fought hard to get him into an apartment. But he died before that could happen. Parker’s story is brutal, but it also says a lot about why it’s so hard to pull someone like him out of homelessness.

This story is part one in a multi-media series on homelessness in New Hampshire :

http://www.nhprdigital.org/series-homeless-in-nh#special-series-homeless-in-nh

In Face Of Immigration Rhetoric, Latinos Grapple With Having A Voice

Olmer Villavicencio talks to his daughter, Jocelyn, about what he's struggling with. These days, that’s how to get his neighbors to see their voice matters this election. Olmer's not an organizer or a politician. He's a guy who knows everybody and, living in New Hampshire, has a front-row seat to the presidential race. He says it's just about getting fellow Latinos to see it that way.

Olmer Villavicencio talks to his daughter, Jocelyn, about what he's struggling with. These days, that’s how to get his neighbors to see their voice matters this election. Olmer's not an organizer or a politician. He's a guy who knows everybody and, living in New Hampshire, has a front-row seat to the presidential race. He says it's just about getting fellow Latinos to see it that way.

Amid Backlash Against Isolating Inmates, New Mexico Moves Toward Change

Level 6 of New Mexico's state penitentiary in Santa Fe is a dense complex of prison cells, stacked tight. As the gate opens, men's faces press against narrow glass windows. They spend 23 hours a day in solitary.

Level 6 of New Mexico's state penitentiary in Santa Fe is a dense complex of prison cells, stacked tight. As the gate opens, men's faces press against narrow glass windows. They spend 23 hours a day in solitary. Security is so high that talking to one of the inmates, Nicklas Trujeque, requires a guard passing a microphone through the food port of his cell door.

Despite Bans, Pregnant Prisoners Still Shackled During Birth

Across the country, it's common practice to handcuff a pregnant prisoner to her hospital bed while she gives birth.

Photo by Jane Evelyn Atwood

Across the country, it's common practice to handcuff a pregnant prisoner to her hospital bed while she gives birth. Maria Caraballo gave birth to her daughter an entire year after New York passed its anti-shackling law. But she says she was handcuffed for eight hours the day her daughter Estrella was born.

Campus Rape in the North Country (3-Part Series)

One in four female college students will be raped or sexually assaulted before they graduate. Students are more likely to report when they see their school is willing to act aggressively, but in practice, only about 10 percent of perpetrators face expulsion, much less criminal prosecution. What laws and policies are supposed to protect women at college? And why aren't they working?

https://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/story/26936/20141217/campus-rape-in-the-north-country

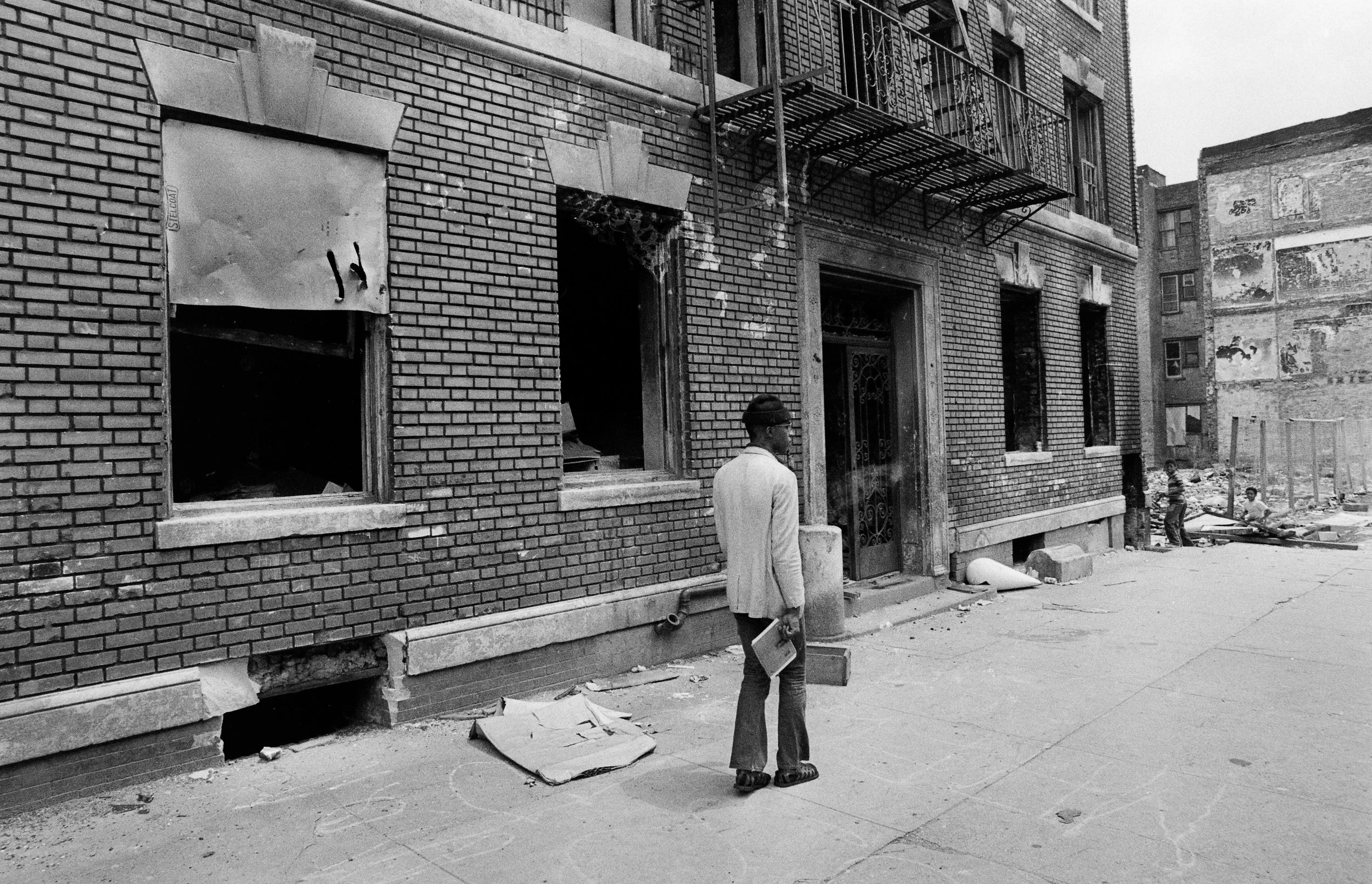

Grappling with 40 Years of the Drug War In Brownsville, Brooklyn

Aaron Hinton says the 40-year drug war in Brownsville has almost made spending time behind bars normal. “It’s subliminally attacking out minds and making us believe that socially this is acceptable.” One out of every 50 men in New York’s prisons comes from Brownsville. The state of New York spends $40 million a year – and this has been going on for generations — locking up black and Hispanic men from this one neighborhood. What does that do to a community?

Brownsville 1972, photo by Winston Vargas

Aaron Hinton says the 40-year drug war in Brownsville has almost made spending time behind bars normal. “It’s subliminally attacking out minds and making us believe that socially this is acceptable.” One out of every 50 men in New York’s prisons comes from Brownsville. The state of New York spends $40 million a year – and this has been going on for generations — locking up black and Hispanic men from this one neighborhood. What does that do to a community?

Dying Inmates in New York Struggle to Get Home

Over the last four decades, New York’s prison population has soared, with many people serving long mandatory sentences for low-level crimes. As a result, the number of elderly inmates is surging—growing by almost eighty percent from 2000 through 2009.

Coxsackie Correctional Facility - Greene County, NY

Many terminally ill inmates are forced to remain behind bars even when they no longer appear to be a threat to society. This is the story of Daryl Bidding’s long struggle to get home before he dies.